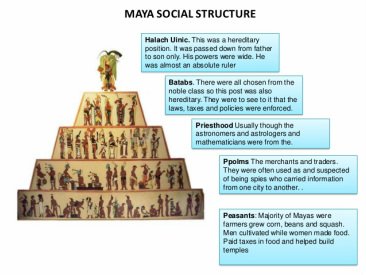

SOCIAL CLASSES

The Maya had a class society. As in other Mesoamerican cultures, an individual’s daily life depended on his or her social class. There were slaves, farmers, artisans and merchants, nobility, priests and leaders. There were also warriors. The highest class was made up of the nobility. In addition to the king, nobles included priests, scribes, government officials, and elite warriors. The middle class consisted of artisans, traders, weavers, potters and other warriors. At the basis of the social order were farmers, other workers and slaves. The Mayan social structure was quite rigid without much room for mobility, even from one generation to the next. From the king down, for example, a Mayan man’s work was inherited from his father. If your father was a farmer, you were a farmer. There were some exceptions, but they were rare. There was a little more flexibility for women. Some women were involved in government, economics and religion. At the same time, however, they were still responsible for caring for the children and running the household, just like their mothers.

Halach Uinic

At the head of each city-state there was a king called “halach huinic” (true man) who had all powers including divine power. The king was considered a sacred ruler, one who ruled by divine right. Believed to be the descendant of a god, a king’s authority was unquestioned and absolute. In Mayan cities the crown was passed down from father to son. In theory, the same family could have ruled forever, or at least until evidence emerged that the king was no longer favored by the gods. Losing in war was a sure sign that a king had lost the favor of the gods. Although rule by a king was more common, a woman could rule and many did. If a woman took power, however, it was usually as a king’s widow or as a prince’s mother. However, many of the Mayan female rulers were quite powerful, and even participated in battles. The first female Mayan ruler in Mayan history was Lady Yohl Ik’nal of Palenque.

Priests

Mayan priests were second in importance, behind only the Mayan kings in their social order. They were the most educated of all the Maya and were considered the keepers of knowledge. They learned to read and write and taught these skills to the children of nobles. They also studied astronomy and astrology and used the complex Mayan calendar to advise on everything from when to plant crops to prophecies for kings, nobles, and commoners. Priests kept track of family lines of succession, especially for Mayan kings. With this combination of skills, one might say that the priests were also Mayan historians. The Maya believed that every aspect of their lives had religious significance and that their priests could speak to the gods. Therefore, one of the most important things priests did was host religious ceremonies.

Because the Maya had so many gods, at least once a month everyone from the king to the common people participated in religious ceremonies in which priests made offerings to the gods. The offering could be food or incense. Occasionally the offering took the form of a human sacrifice. With so many ceremonies, taking charge of such events, speaking to the gods, and interpreting the will of the gods was an important part of a priest’s life.

Nobles

The noble class was the smallest of all Maya social classes, but was the richest and most powerful. Nobles were people who had royal blood but were not the king. They were government officials, bailiffs, governors and city administrators, scribes and tax collectors, as well as military leaders. According to Mayan beliefs, nobles occupied a space between gods and humans. With that high social position, they had to serve both. They lived in large stone houses in the center of Mayan cities. Their diet was similar to that of other classes, but they probably ate more meat and enjoyed a delicious chocolate drink every day. In exchange for the benefits received, the nobles regularly made offerings to the gods. In addition to their beautiful homes and larger meals, Mayan nobles also liked to wear elegant clothing and elaborate jewelry and covered their bodies in tattoos. For the Maya, just like other ancient civilizations, the life of a noble was easier than for a commoner. The life of a nobleman, however, was not without its drawbacks. If a noble was captured in war, he was much more likely to be tortured and sacrificed to the gods. While captured commoners could also be sacrificed, they were more likely to end up as slaves.

Warriors

Warriors were important to the Mayan way of life and the work of the warrior was highly respected. The Mayans were fierce warriors. Before going into battle, warriors created a confidence-building shield. It was a flat, round circle covered in images representing all the wonderful things they had accomplished and all the battles they had won. The weapons used by Mayan warriors typically fell into two categories. Long-range weapons included spears, air guns, slings, and, later, bows and arrows. However, since the warrior’s goal was more often to capture than to kill, the most commonly used weapons were designed for hand-to-hand combat.

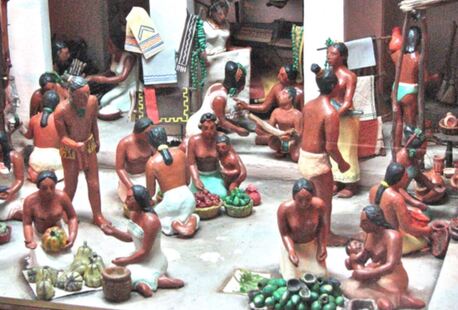

Artisans and merchants

As trade between cities grew and became more important, groups of people formed to manage major construction projects in cities and to create goods for trade. These people constituted the middle class in Mayan society. The Mayan middle class included artisans, merchants, minor warriors.

Mayan artisans had a slightly easier life compared to the hard physical labor required of common people who worked on farms. They spent their days creating beautiful objects such as jewelry, textiles, pottery, cloaks, and feather headdresses.

Most of the goods produced by Mayan artisans were intended for the noble class and royalty but they could also sell their goods at the market with the profit going to the family. After paying tribute to the king and taxes to the community, artisans could use the rest of what they earned to improve their lives.

Mayan merchants traded two types of goods, everyday items and luxury items. They often transported their goods along trade routes far away in canoes so large they could hold up to twenty people plus trade goods. Mayan merchants exchanged surplus items for items they needed.

Because children typically inherited work from their parents, entire families of artisans and merchants could be seen within Mayan communities involved in the same work. Although the families of artisans and merchants could live in slightly larger houses, the pattern of their daily life was much the same as that of the peasants.

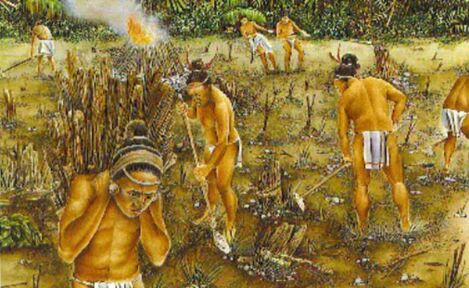

Common men

Most Mayans lived in the lower classes which were made up of commoners. Most of the common people were peasants. Once their crops were harvested, farmers often went to work building the pyramids and temples found in their beautiful cities. While some commoners might also work as serfs of the noble class or in limestone quarries, most commoners were farmers who passed down their lives of hard work from generation to generation. Mayan farming families started their day early. Men and boys went to the fields or construction sites and the women went to work in their homes, cooking, raising children, tending the vegetable gardens and weaving fabrics for their own clothes and for the market. Ordinary people worked hard but ate well. However, life was not all work for the common Mayan people. At least every month there was a religious festival in the city and everyone went to sing, dance and worship their many gods.

Slaves

Slaves were the lowest class in Mayan society. They were usually orphans, prisoners of war, criminals, or the children of slaves. While they were not necessarily mistreated by their owners, slaves still had no rights or privileges in Mayan society. Basically, the slave’s only function in society was to perform all manual labor. For this reason, Mayan society depended on them. Slaves worked in the homes of noble families. Additionally, slaves helped build the great Mayan temples. They were also those most frequently used for the Mayan ritual of human sacrifice.